Well, it’s time to draw the curtains and turn out the lights.

Despite some hiccups here and there, I managed to finish where I wanted, with the most recent major studio slasher release, the Nightmare on Elm Street remake.

When I started this all, I wanted to see if I could come to some conclusions about the resiliency of the Slasher film and the iconic slasher characters in particular. I had intended to address the Scream franchise, but time and circumstances prevented me from doing so. I haven’t seen Scream in over six years, so writing about it without screening it again would do both the film and myself a disservice. So, no Scream, nor any of its progeny (I Know What You Did Last Summer, Valentine, Urban Legend, etc.).

So, what did I learn?

These films really do live or die based on the competency and imagination of the director. The best slasher films have someone at the helm with fresh ideas, someone capable of delivering compelling imagery and a coherent narrative. You know, the same things every good movie needs.

If you don’t have a director who has the skill or finesse of John Carpenter or the fearlessness of a Tobe Hooper, it helps to distract us with the taboo and do so early and often – don’t wait thirty minutes between the pre-credits kill and the next victim.

Tying into that, a good slasher film is well-constructed and well-paced. That means that set pieces are staged at the right time, and have the right impact on the narrative. My Bloody Valentine is a great example of this. There’s never too much dead time (heh) – the plot clicks away and yet there’s ample space for characters to have their moments of distinction and relevancy. Which brings me to…

Slashers are only as memorable as the scenes in which they do their business. This isn’t just about the kill effects, although those are a big part of it. It also has to do with how satisfying the kill is, which has to do with the characterization of the people being killed prior to their demise. There are plenty of AWESOME kills in slasher film history that stand alone – scenes that kick ass without any context whatsoever. I’m not talking about those – I’m talking about the qualities that make the character doing the killing memorable. For that, context is important; who is being killed and how they’re killed must be balanced against the audience’s love/hate for the character.

But on the topic of those awesome kills I mention above, beyond the context of the narrative, the greatest slasher films have those individual moments, scenes, or visuals that transcend the plot. I’m talking about those moments that you take a mental snapshot of and carry around with you for mental reference whenever you see the film’s title or someone mentions the movie in passing. Often these moments are the ‘kills,’ but they don’t have to be – many of Halloween’s most memorable shots, for example, evoke the uncanny rather than spotlight an act of violence. This is cinema – you can’t dismiss the importance, the critical vitality, of the image. Hell, Kubrick understood that and that’s why, scene-for-scene, The Shining has more ‘iconic’ shots or scenes than maybe any other horror film in history. But look back over the past month and you’ll see that Hooper, Carpenter, and, yes, even Craven all bring this awareness to the table as well. If a slasher doesn’t contain one or more of these moments, it’s likely to fade from memory. I caught myself popping in three different films over the past month that I had completely forgotten I had already watched within the past two years – there weren’t any significant images that made them memorable in any way, shape, or form.

Nearly all of the films I’ve written about have at least one, and often more, signature moments or visuals that make them more than just another title in the back-catalogue.

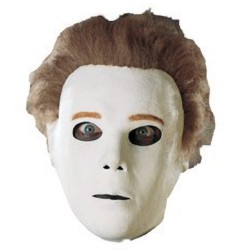

The most commercially and culturally successful slasher characters are somewhat macabre looking, but not grotesque. This also has to do with the films in which these characters feature. You won’t find a more graphic studio franchise series than the Friday the 13th films, but they’re not disturbing the way Texas Chain Saw Massacre is. A studio marketing team can sell a Friday or Halloween film with minimal fuss because they’re essentially monster movies and monster movies, no matter how much subtext they contain, are essentially fantasies. A film like Texas Chain Saw has the vapors of something altogether different at play.

I mean, I’ve seen Jason masks and Michael masks on sale at Walmart, but if you want to get yourself a mask of simulated human skin, costume specialty shops and on-line retailers are your best bet.

The point I’m making here is that while slasher films are exploitation pictures, there’s a world of difference between Last House on The Left and House on Sorority Row. A good slasher film is about thrills and, ultimately, entertainment. Yes, it’s a special brand of entertainment, but it’s no more deviant in its appeal than Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky or the Expendables.

The best slasher films keep it well under 2 hrs and the plots aren’t too complicated. They give the slasher himself just enough backstory to make him stand out and then let his mask and his methods be the discriminator. Ultimately, how the director tells the story is far more important than whatever goofy motive the killer has for hacking people up anyway.

It helps if the film has a sense of humor, even if it’s a black one. Humorless films tend, more often than not, to be dull slogs that don’t encourage repeat viewing. Notice I said film, and not character. In my opinion, slashers can be a source of humor but they shouldn’t be comedians, but this is just my own opinion. As ambivalent as I am about Freddy and his comedy killer kin, a big part of their appeal, and the appeal of the Scream franchise as well, is that they’re playful.

Finally, having said that, I think the era of self-referential, “nudge nudge, wink wink” slasher film has run its course, thank you very much Scream and Behind the Mask. It’s possible to make a great slasher film without the characters referring to the fact that they’re in a slasher film. The best way to respond to the slasher formula is use it and make a great slasher film with it. After all, they still make great heist movies, great war movies, and great romantic comedies…these all have their formulas, their tropes. Meta can only take you so far, and then you become Scary Movie.

Ultimately, I’m glad I committed myself to this little project, even if nobody read it (LOL). In hindsight, I would have put on my editor’s hat on a little more firmly and cut each entry by about thirty percent, but my goal here was to commit to some long form writing that would force me to actually sit at the keyboard and put some sentences together for long periods of time. At this point, I have written approximately 20,000 words for this series. Not too shabby.

That said, my wife is grateful I’m done and no longer spending the wee mornings watching knives plunge into screaming women’s chests and spending my evenings scanning Google Images for stills of the same. She’s been really patient and I thank her.

In the meantime, it’s Halloween so I intend to spend the day getting my kids ready for trick or treating and watching some movies that are a little more, shall we say, benign – maybe some Mad Monster Party or It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown.

Happy Halloween everyone, and thanks for reading.